Context:

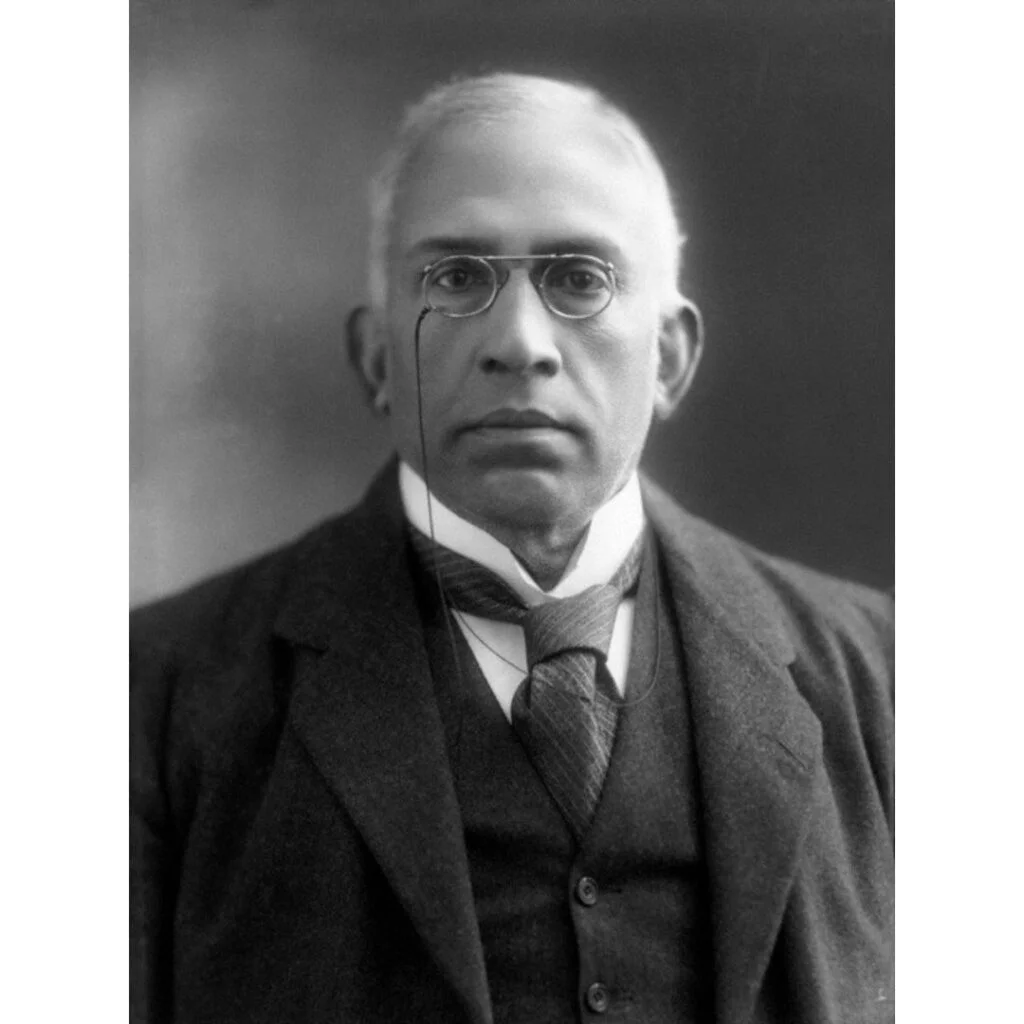

Recently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid tribute to Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair on the 106th anniversary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

Who Was Chettur Sankaran Nair?

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair (1857–1934) was a distinguished Indian jurist, nationalist, and reformer who played a significant role in India’s early struggle against British colonial rule.

Early Life and Education:

- Born on July 11, 1857, in Mankara, Palakkad district (Kerala), to Parvathy Amma Chettur and Mammayil Ramunni Panicker, he began practicing law in the Madras High Court in 1880.

- In 1884, he was appointed to a committee by the Madras government to inquire into the Malabar district.

Political and Legal Career:

- 1897: Presided over the First Provincial Conference in Madras.

- 1897: Became the first Keralite as well as the youngest to be elected President of the Indian National Congress at its Amravati session.

- 1907: Appointed Advocate-General of the Madras Presidency.

- 1908–1915: Served as Permanent Judge of the Madras High Court.

- 1912: Knighted by the British Crown for his legal services.

In several other significant cases, he upheld the validity of inter-caste and inter-religious marriages, affirming his strong belief in social equality and reform through the judicial system.

1914: In Budasna v. Fatima, Nair ruled that those who converted to Hinduism could not be treated as outcastes, reinforcing the right to religious conversion without social penalty.

- In several other significant cases, he upheld the validity of inter-caste and inter-religious marriages, affirming his strong belief in social equality and reform through the judicial system.

Role in National Reform:

- 1915: Appointed Member for Education in the Viceroy’s Council.

- Belief in Self-Government: Nair strongly believed in India’s right to self-governance and thus played a critical role in expanding provisions in the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919, which introduced a system of dyarchy in the provinces and increased Indian participation in administration.

- 1919: Resigned from the Viceroy’s Council to protest the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and martial law in Punjab. Authored strong minutes of dissent calling for constitutional reforms—many of which were eventually accepted.

- 1920–1921: Served as Councillor to the Secretary of State for India in London.

- 1925: Appointed to the Indian Council of State.

- Passed away in 1934 at the age of 77.

1922: He later wrote a book, Gandhi and Anarchy (1922), criticizing Gandhi’s methods of non-violence, civil disobedience, and non-cooperation and also accused Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab during the massacre for following policies that led to the deaths.

1924: Based on the above criticism, O’Dwyer sued Nair for defamation in England, the 12-member all-English jury sided with O’Dwyer. The verdict angered Indian nationalists, reinforcing the belief that the British legal system was inherently biased.

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre (April 13, 1919)

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre occurred in Amritsar, Punjab, on April 13, 1919.

It was a tragic culmination of the tensions stirred by the Rowlatt Act.

- The Rowlatt Act, officially known as the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919, was a law passed by the British government in India to suppress dissent and revolutionary activities.

A large crowd of about 20,000 people had gathered at Jallianwala Bagh to celebrate Baisakhi, a religious festival, and to protest the arrest of local leaders Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr Satyapal.

The crowd was unaware of the martial law orders, including a ban on public gatherings.

Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, in charge of enforcing martial law, arrived at the scene with his troops, surrounded the gathering, and opened fire without warning.

Official British records claimed 379 dead and over 1,100 wounded, while Indian sources and other estimates suggest much higher casualties.

The massacre led to widespread outrage:

- Rabindranath Tagore renounced his knighthood in protest, and M.K. Gandhi gave up the title of Kaiser-i-Hind. Gandhi, overwhelmed by the violence, called off the non-cooperation movement on April 18, 1919.